Article Plan: A Pocket Guide to Writing in History (as of 11/29/2025)

This guide offers essential strategies for historical research and writing‚ covering source evaluation‚ argument development‚ and effective presentation techniques․

It emphasizes backing up opinions with evidence‚ understanding historical discourse‚ and adapting research for diverse formats like papers and presentations․

Furthermore‚ it details efficient methods for locating books‚ journals‚ and primary sources‚ alongside crucial style and grammar considerations for clarity․

I․ Pre-Research Considerations

Before diving in‚ define your research question clearly‚ identifying key concepts and terms to establish a focused scope․

Consider potential limitations early on‚ ensuring a manageable and insightful historical investigation from the outset of your work․

Defining Your Research Question

Formulating a strong research question is paramount․ It’s the foundation upon which your entire historical argument will rest‚ guiding your investigation and shaping your analysis․ Avoid overly broad questions; instead‚ strive for specificity․ A well-defined question isn’t simply about what happened‚ but how and why it happened․

Consider what genuinely interests you within the broader historical context․ This intrinsic motivation will sustain you through the research process․ Refine your initial ideas through preliminary reading‚ identifying gaps in existing scholarship or areas ripe for reinterpretation․

A good research question should be arguable‚ meaning reasonable people could disagree with your proposed answer․ It should also be researchable‚ relying on available sources for evidence․ Finally‚ ensure it’s focused enough to be addressed within the constraints of your assignment’s length and scope․

Identifying Key Concepts & Terms

Once you’ve defined your research question‚ pinpoint the core concepts and terms central to your investigation․ These aren’t just keywords for searching; they represent the fundamental ideas you’ll be analyzing․ Consider how these terms were understood within the historical context – meanings evolve over time․

Creating a list of these terms allows for focused research and ensures consistent application throughout your essay․ Explore related terms and synonyms to broaden your search and uncover nuanced perspectives․

Be mindful of potentially ambiguous terms that might have multiple interpretations․ Clearly define how you are using these concepts within your argument․ This demonstrates analytical rigor and prevents misunderstandings․ A glossary of terms can be helpful‚ especially for complex or specialized vocabulary․

Establishing Scope & Limitations

Defining the scope of your research is crucial for a manageable and focused historical inquiry․ History is vast; attempting to cover everything is unrealistic․ Clearly delineate the chronological period‚ geographical area‚ and specific aspects of the topic you will address․

Acknowledging limitations demonstrates intellectual honesty․ What aspects are you not covering‚ and why? This might be due to source availability‚ time constraints‚ or the specific focus of your argument․

Explicitly stating these boundaries prevents accusations of overreach and allows you to delve deeper into the chosen area․ A well-defined scope strengthens your analysis by providing a clear framework for your investigation and argument․ Be realistic about what you can achieve within the assignment’s parameters․

II․ Source Evaluation & Selection

Carefully assess sources for authorship‚ bias‚ and reliability․ Utilize academic databases and indexes to find relevant books‚ journals‚ and primary materials efficiently․

Types of Historical Sources: Primary vs․ Secondary

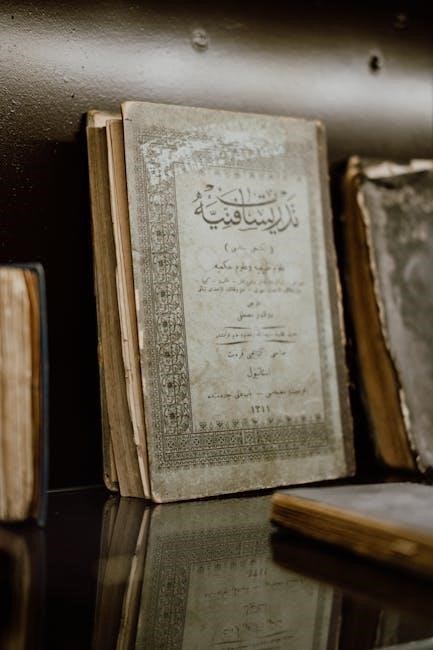

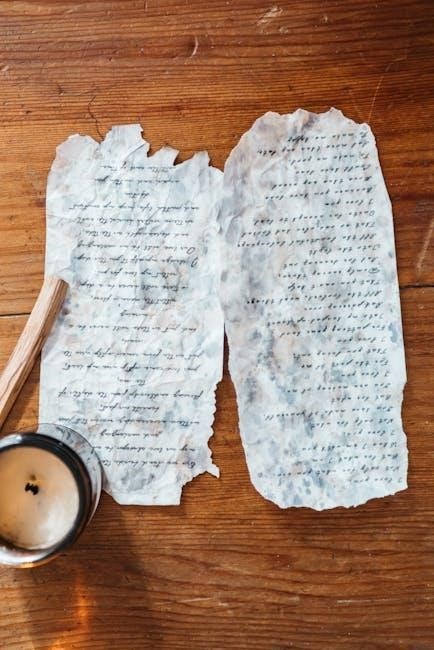

Understanding the distinction between primary and secondary sources is fundamental to historical research․ Primary sources offer firsthand accounts or direct evidence from the time period under investigation – think diaries‚ letters‚ speeches‚ official documents‚ and artifacts․ These sources allow historians to engage directly with the past‚ interpreting events through the voices of those who experienced them․

Conversely‚ secondary sources analyze‚ interpret‚ or evaluate primary sources․ These include books‚ journal articles‚ and biographies written by historians about the past․ While invaluable for providing context and scholarly analysis‚ secondary sources represent an interpretation‚ not a direct experience․

The best historical work utilizes both types of sources‚ critically evaluating secondary interpretations while grounding arguments in the evidence provided by primary materials․ Selecting appropriate sources depends on your specific research question‚ ensuring relevance and analytical depth․

Evaluating Source Authorship & Bias

Critically assessing source authorship and potential bias is crucial for responsible historical interpretation․ Every source is created within a specific context‚ reflecting the author’s perspective‚ beliefs‚ and intentions․ Consider the author’s background: their social status‚ political affiliations‚ and personal experiences all shape their viewpoint․

Ask yourself: What was the author’s purpose in creating this source? Were they attempting to persuade‚ inform‚ or simply record events? Recognizing potential biases – conscious or unconscious – doesn’t invalidate a source‚ but it necessitates careful interpretation․

Look for evidence of agenda or prejudice‚ and compare accounts from multiple sources to identify corroboration or conflicting perspectives․ A nuanced understanding of authorship allows for a more accurate and balanced historical analysis․

Assessing Source Reliability & Credibility

Determining a source’s reliability and credibility is paramount in historical research․ Prioritize sources authored by experts in their field – books‚ journal articles‚ and chapters in edited volumes are generally strong starting points․ Scrutinize the publisher and the peer-review process‚ if applicable‚ as these indicate a level of scholarly rigor․

Consider the source’s internal consistency: Does the evidence presented support the author’s claims? Cross-reference information with other sources to verify accuracy and identify potential discrepancies․ Be wary of sources lacking clear documentation or relying on unsubstantiated assertions․

Remember that even scholarly sources can have limitations․ A critical approach involves acknowledging these limitations and considering alternative interpretations․

Utilizing Academic Databases & Indexes

Academic databases and indexes are indispensable tools for historical research‚ offering efficient access to a wealth of scholarly materials․ These resources compile citations and abstracts of books‚ journal articles‚ and other relevant publications‚ streamlining the search process․

Explore databases specific to history‚ such as JSTOR‚ Project MUSE‚ and America: History & Life․ Utilize keywords and Boolean operators (AND‚ OR‚ NOT) to refine your searches and target relevant results․ Don’t overlook the power of subject headings to broaden or narrow your focus;

Remember to consult your institution’s library website for access to subscribed databases and guidance on effective search strategies․

Finding Books & Journal Articles

Locating relevant books and journal articles is central to historical research․ Begin with your course guide’s suggested readings – these often represent prominent sources in the field․ Explore library catalogs using keywords related to your research question‚ and examine the bibliographies of these initial sources․

Footnotes are invaluable; they direct you to other key works on the topic․ Utilize academic databases like JSTOR and Project MUSE for journal articles․ When evaluating potential sources‚ prioritize those written by experts‚ such as books and articles from peer-reviewed journals․

Aim to consult more than the minimum number of academic sources required for your assignment‚ fostering a comprehensive understanding of the historical context․

III․ Research Strategies

Effective research involves strategic searching‚ utilizing both electronic databases and print indexes‚ alongside careful examination of footnotes and bibliographies for key sources․

Effective Search Strategies (Electronic & Print)

Mastering search techniques is crucial for efficient historical research․ Begin by identifying key concepts and terms related to your research question‚ then experiment with different combinations in electronic databases․

Utilize Boolean operators (AND‚ OR‚ NOT) to refine searches and broaden or narrow results․ Don’t limit yourself to online resources; print indexes and bibliographies remain valuable tools․

Explore academic databases and indexes to uncover scholarly articles and books․ When a promising source appears‚ meticulously examine its footnotes and bibliography․

These often lead to other prominent sources in the field‚ creating a snowball effect of discovery․ Remember to adapt your search terms based on initial findings‚ continually refining your approach for optimal results․

Consider variations in spelling and terminology‚ as historical language can differ from modern usage․ A systematic and adaptable search strategy will significantly enhance your research process․

Utilizing Footnotes & Bibliographies

Footnotes and bibliographies are cornerstones of historical scholarship‚ providing transparency and enabling readers to verify your sources․ They demonstrate academic rigor and allow for further exploration of the topic․

Carefully examine the footnotes in books and journal articles – they act as roadmaps to other relevant scholarship‚ revealing prominent sources in the field․ This is a powerful method for expanding your research․

Bibliographies offer a comprehensive overview of the sources consulted by an author‚ providing a valuable starting point for your own investigation․

Pay attention to the types of sources cited; this can indicate influential works and key debates within the historical community․

Properly formatted footnotes and bibliographies are essential for avoiding plagiarism and upholding academic integrity‚ showcasing your commitment to responsible scholarship․

Identifying Prominent Sources in the Field

Discovering key works is crucial for navigating historical research․ Prominent sources represent foundational scholarship and ongoing debates within a specific area of study․

Begin by examining the bibliographies of respected books and articles; these often reveal frequently cited and influential texts․ Trace the scholarly conversations through these references․

Pay attention to authors consistently appearing in your initial readings․ Their repeated presence suggests significant contributions to the field․

Consult course syllabi and reading lists from relevant history courses at reputable institutions – these often highlight essential texts․

Utilize academic databases and indexes to identify highly cited articles and books‚ indicating their impact and relevance within the historical community․

Finding & Using Images‚ Speeches & Maps

Visual and auditory sources enrich historical analysis‚ offering unique perspectives beyond textual evidence․ Locating these materials requires diverse strategies․

Online archives and digital collections (like the Library of Congress) are invaluable for finding images‚ maps‚ and digitized speeches․

University libraries often hold special collections of historical photographs‚ maps‚ and recordings․ Explore their holdings․

When using these sources‚ critically evaluate their context‚ origin‚ and potential biases․ Consider the creator’s purpose and intended audience․

Always provide detailed captions explaining the source’s significance and how it supports your argument․ Proper attribution is essential․

Maps reveal spatial relationships and changing boundaries‚ while speeches offer insights into contemporary thought and rhetoric․

IV․ Developing Your Historical Argument

Crafting a strong historical argument requires a clear thesis supported by interpreted evidence‚ avoiding presentism and anachronism for nuanced analysis․

Constructing a Thesis Statement

A compelling thesis statement is the cornerstone of any historical essay‚ serving as a concise declaration of your argument․ It’s not merely an observation‚ but a claim that requires evidence and interpretation to support․ Think of it as a roadmap for your reader‚ outlining the central point you intend to prove․

Effective thesis statements are specific and focused‚ avoiding vague language or broad generalizations․ They should directly address the research question and offer a unique perspective on the historical topic․

Remember‚ instructors expect you to back up your opinions with historical evidence․ Your thesis should hint at the evidence you’ll use․ A strong thesis isn’t static; it can evolve as your research progresses‚ but it provides essential direction throughout the writing process․

Consider it a working hypothesis that you refine and defend through rigorous analysis of historical sources․

Supporting Arguments with Evidence

Once you’ve established a thesis‚ the crucial next step is providing robust evidence to support your claims․ Historians don’t simply assert opinions; they build arguments based on careful analysis of historical sources․ This means drawing upon books‚ journal articles‚ primary sources‚ and other credible materials․

Each argument within your essay should be directly linked to specific evidence‚ clearly demonstrating how the source supports your interpretation․ Avoid generalizations and instead focus on detailed examples and specific data․

Remember to consider a range of evidence‚ aiming to use more than the minimum number of sources required․

Footnotes and bibliographies are essential for acknowledging your sources and allowing readers to verify your claims․ A good essay demonstrates a thorough engagement with the existing scholarship on the topic․

Interpreting Historical Evidence

Historical evidence rarely speaks for itself; it requires careful interpretation․ This involves analyzing the source’s context‚ authorship‚ and potential biases to understand its meaning and significance․ Don’t simply present evidence – explain what it means and how it supports your argument․

Consider multiple perspectives and interpretations․ Historians often disagree‚ and acknowledging these debates strengthens your analysis․

Be mindful of avoiding presentism and anachronism․

Presentism is judging the past by present-day values‚ while anachronism is imposing modern concepts onto past events․

Instead‚ strive to understand the past on its own terms‚ recognizing the different beliefs‚ values‚ and constraints of the time period․

Avoiding Presentism & Anachronism

A crucial skill in historical writing is avoiding presentism and anachronism․ Presentism involves judging past actions based on contemporary values‚ distorting understanding․ Anachronism imposes modern concepts or technologies onto earlier periods‚ creating inaccuracies․

Instead‚ strive to understand the past within its own context․ Recognize that people in the past held different beliefs‚ faced unique constraints‚ and operated under different social norms․

Empathy is key‚ but not justification․ Understanding motivations doesn’t equate to condoning actions․

Carefully consider the language used․ Avoid terms that are anachronistic or reflect modern biases․

Focus on what people at the time believed and why‚ rather than imposing your own interpretations or judgments․

V․ Writing & Structuring Your Essay

Crafting a compelling history essay requires a clear structure: introduction setting context‚ body paragraphs developing arguments with evidence‚ and a reflective conclusion․

The introduction is paramount; it establishes the historical landscape for your argument․ Begin by broadly introducing the topic‚ gradually narrowing your focus to the specific research question․

Avoid jumping directly into details; instead‚ provide necessary background information to orient the reader․

Clearly articulate the historical significance of your topic – why does it matter?

Most importantly‚ conclude your introduction with a concise thesis statement․

This statement should present your central argument and offer a roadmap for the essay’s development․

A strong introduction doesn’t just state what you’ll argue‚ but also how you’ll support your claims‚ setting the stage for a persuasive and well-supported historical analysis․

Remember‚ context is key to engaging your reader and demonstrating the relevance of your historical inquiry․

Body Paragraphs: Developing Your Argument

Body paragraphs form the core of your historical argument‚ each dedicated to supporting a specific aspect of your thesis․

Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that directly relates to your central claim․

Follow this with compelling historical evidence – facts‚ examples‚ quotes from primary sources – to substantiate your point․

Crucially‚ don’t simply present evidence; interpret it․

Explain how the evidence supports your argument and connects back to your thesis․

Historians expect interpretations‚ not just recitation of facts․

Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs to create a cohesive and logical flow of ideas‚ building a robust and persuasive historical narrative․

Summarizing & Reflecting

Your conclusion shouldn’t simply rehash your introduction; instead‚ synthesize your argument and offer a thoughtful reflection․

Begin by briefly summarizing your main points‚ reinforcing your thesis without being overly repetitive․

Consider the broader implications of your research․

What does your analysis contribute to the existing historical conversation?

Acknowledge any limitations of your study or areas where further research is needed․

Avoid introducing new evidence or arguments in the conclusion․

Instead‚ aim for a concise and impactful closing statement that leaves the reader with a clear understanding of your argument’s significance and its place within the larger historical context․

VI․ Presentation & Refinement

Mastering formatting and citation styles—Chicago‚ MLA—is crucial․

Refine style‚ grammar‚ and proofread meticulously for accuracy‚ adapting your work for papers‚ presentations‚ or websites effectively․

Formatting & Citation Styles (e․g․‚ Chicago‚ MLA)

Consistent formatting and precise citation are paramount in historical writing․ Different instructors and publications adhere to specific styles—most commonly Chicago or MLA—demanding meticulous attention to detail․

Understanding these styles involves mastering rules for footnotes‚ endnotes‚ bibliographies‚ and in-text citations․ Incorrect citations not only diminish credibility but can also be considered plagiarism․

Consult style manuals or online resources (like Purdue OWL) to ensure accuracy․ Pay close attention to nuances like date formats‚ author names‚ and punctuation within citations․

Furthermore‚ adhere to specified formatting guidelines for margins‚ font size‚ and spacing․ A polished presentation demonstrates respect for the discipline and enhances the clarity of your argument‚ allowing readers to easily verify your sources and engage with your scholarship․

Style & Grammar Considerations

While not an English course‚ clear and concise writing is crucial for effective historical communication․ Strong style and impeccable grammar enhance your ability to convey complex ideas persuasively․

Avoid colloquialisms‚ contractions‚ and overly casual language; maintain a formal‚ academic tone․ Prioritize precision in word choice‚ ensuring terms accurately reflect historical context․

Vary sentence structure to maintain reader engagement and avoid monotony․ Active voice generally strengthens prose‚ but judicious use of passive voice can be appropriate․

Pay attention to paragraphing; each should focus on a single‚ coherent idea supporting your overall argument․ Utilize transition words to create logical flow between sentences and paragraphs‚ and always proofread carefully for errors in grammar‚ spelling‚ and punctuation․

Proofreading for Accuracy

Meticulous proofreading is paramount in historical writing‚ extending beyond simple grammar and spelling checks․ Verify all factual claims‚ dates‚ names‚ and places against your sources – even seemingly minor errors can undermine credibility․

Scrutinize your citations for consistency and adherence to the chosen style guide (Chicago‚ MLA‚ etc;)․ Ensure every source listed in your bibliography is accurately referenced within the text‚ and vice versa․

Read your work aloud; this helps identify awkward phrasing and grammatical errors often missed during silent reading․ Consider asking a peer to review your essay for a fresh perspective․

Pay close attention to quotations‚ ensuring they are transcribed exactly and properly attributed․ A final‚ careful review before submission demonstrates professionalism and respect for the historical record․

Adapting to Different Formats (Papers‚ Presentations‚ Websites)

Historical research often demands adaptation across various formats․ Traditional research papers prioritize detailed argumentation and comprehensive sourcing‚ adhering to strict academic conventions․

Oral presentations require condensing complex arguments into concise‚ engaging narratives‚ often supplemented by visuals like images‚ maps‚ or timelines․ Focus on key takeaways and clear delivery․

Websites necessitate a different approach – shorter‚ more accessible content with a focus on visual appeal and user experience․ Consider incorporating interactive elements and multimedia․

Regardless of the format‚ maintain historical accuracy and scholarly rigor․ Tailor your language and level of detail to the intended audience‚ ensuring clarity and impact․

Understanding Historical Discourse & Narrative

Historical writing isn’t simply recounting facts; it’s constructing a narrative․ Historians interpret evidence and present arguments within a specific discourse‚ shaped by prevailing methodologies and perspectives․

Recognize that historical narratives are interpretations‚ not absolute truths․ Different historians may offer varying accounts based on their sources‚ biases‚ and analytical frameworks․

Be aware of the language used – it can reveal underlying assumptions and perspectives․ Analyze how historians frame events and construct their arguments․

Understanding this dynamic allows you to critically evaluate historical scholarship and develop your own nuanced interpretations‚ contributing to the ongoing conversation within the field․